How the Christian Creeds Got That Way

The creeds elevated the beliefs of one group of early Christians—and banished the beliefs of the others.

A distinctive feature of Christianity is the prevalence and importance of creeds—notably the Apostles’ Creed and the Nicene Creed—recited today by many millions of churchgoers each week around the world. I memorized both as a child raised in a Lutheran church in the mid-twentieth century, but always found them off-putting. As a teenager, I realized what it was that bothered me about them: They seemed needlessly legalistic and exclusionary—in a way that I came to think of as being essentially un-Christian. (I’ve written about this in a little more detail in this post).

As I began studying Early Christianity, much later in life, I’ve learned more about the creeds, and have a better understanding of how they got that way. A few of my insights:

The formation of the creeds was bound inextricably with the rise of what modern scholars refer to as proto-orthodox Christianity—one of many forms of Christianity practiced in the first three centuries of the Common Era. The creeds, on the one hand, are summaries of what proto-orthodox Christians believed, but on the other hand are denials of what a plurality—and in some regions, perhaps a majority—of other early Christians believed.

The exclusionary nature of the creeds was, as we might put it today, a feature, not a bug. The proto-orthodox Christians were not content to disagree with Christians who held different interpretations of the nature of God and the teachings of Jesus. They insisted that their way was the only way, and that those Christians who disagreed were thus not Christians at all. As the proto-orthodox church became more powerful, supplanting and suppressing rivals, it went on to anathematize (curse) other forms of Christianity, excommunicate their adherents as “heretics,” and criminalize them. (Up to and including, executing them.)

The creeds we know today are not as ancient as you might think. They first appear in the fourth century, nearly three hundred years after the crucifixion of Jesus. The first version of the Nicene Creed was promulgated in 325, and edited and revised in 381 into the text still in use today. An early version of what became the Apostles’ Creed dates to about 400, but the form recited today was not finalized until the ninth century.

The English word “Creed” come from the Latin credo, which means “I believe” (the first word in the Latin Apostles’ Creed. The Greek word which was translated as “creed” is σύμβολον, (symbolon), which originally meant half a torn or broken object which, fitted with the other half, verified the bearer's identity. (Think of spy stories where the secret agent slips half a torn postcard under a door to establish his or her identity—confirmed when the recipient fits it together with the other half.) One of the first Christian Creeds known—a predecessor of what became the Apostles’ Creed, was called “The Old Roman Symbol.” The implication is that if you will not recite the creed, you cannot identify yourself as a Christian.

Creeds and Early Christianities

Modern critical scholars of early Christianity have shown that there were a wide variety of beliefs among those who considered themselves Christian in the first centuries after Jesus. In fact, they often use the term early Christianities, rather than referring to early Christianity as a single, uniform belief system. As M. David Litwa, a scholar of ancient Mediterranean religions with a focus on the New Testament and early Christian history, explains:

Over the past fifty years…. early Christianity has been redescribed as a pluralist movement, featuring several different kinds of Christians, bound together in fairly porous groups. Labelling some of these groups “mainstream” and others “heretical,” marginal,” or otherwise “deviant” is generally seen as unhelpful because it reinscribes—often in subtle ways—ancient heresiological categories. Similarly, labelling one group the “majority” or “great” church makes little sense when we have no solid demographic data for the diverse locales in which Christianity took root. In 1934, German historian Walter Bauer argued that in certain areas—for instance, the cities of Edessa and Alexandria—a Christianity later labeled “heretical” was in fact the common form during the second century CE.

One of these early Christianities, referred to by modern critical scholars as proto-orthodoxy, defeated or outlasted the others over the first several centuries CE, culminating in its adoption as the state religion of the Roman Empire—which extended at the time from Western Europe to Northern Africa and Western Asia—and went on to form the Roman Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox churches.

The closer you look at the various beliefs of early Christians, the more apparent it becomes that one of the purposes of the creeds—perhaps the main purpose—was to exclude Christians who had different beliefs about the nature of God, his relationship with Jesus, and the nature Jesus and of the Holy Spirit.

Consider the opening of the Apostles’ Creed: “I believe in God the Father Almighty, creator of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ, his only son, our Lord…” This comports with the views of proto-orthodoxy, but it specifically denies the beliefs of other Christians of the time.

Among those excluded by the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds were followers of Marcion, for example, (who taught that the God who sent Jesus to earth was a transcendent—and different—God than the God of the Hebrew Bible who created the world). Also excluded were followers of the Christian “gnostic” teacher Valentinus, who, believed that there were a variety of gods in the Christian pantheon (one of whom was a female deity named Wisdom), and that the key to immortality had much to do with self-knowledge. Both Marcion and Valentinus were teaching (and attracting significant numbers of followers) in the Roman Empire in the mid-second century, in direct competition with the proto-orthodox church.

Marcion and Valentinus were denounced by the proto-orthodox as heretics, and it’s worth focusing on the word. “Heresy” It comes from the Greek αἵρεσις (haeresis), which originally meant “a choice,” or “a system of principles,” and by the Common Era could mean “a school of thought” or a “sect.” The proto-orthodox church adopted the word to describe, in a pejorative way, any denial or doubt about a core doctrine of the faith as proto-orthodoxy defined it.

Among the other heresies that the creeds denied were: Arianism, which held that Jesus was a creation of God, and therefore distinct from God; Adoptionism, the belief that Jesus was not born the Son of God, but was adopted at his baptism, resurrection or ascension; Montanism, which focused on prophetic revelations from the Holy Spirit, and Docetism, the belief that Jesus was pure spirit and that his physical form was an illusion.

Creating the Creeds

The development of the creeds seems to have been a continuing project of proto-orthodox Christianity, as church leaders refined their own ideas of God’s relationship with the world and set themselves in opposition to those they had defined as heretics.

Among the biblical roots of the creeds are “baptismal interrogations”—questions put to converts at their conversion. They were versions of Jesus’s “Great Commission” to his disciples, after his resurrection, in the Gospel of Matthew: “Go therefore, instruct all the gentiles, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.”

The other predecessors of the creeds are individual affirmations of belief, often called “rules of faith,” found in Christian writings from the mid-second century onward. As scholars Wolfram Kinzig and Markus Vinzent explain in a 1999 journal article: “These are doctrinal summaries which were ad hoc formulated in theological controversy especially against Gnostics.” They note that while rules of faith resemble creeds, their overall structure was not fixed, and their wording varied. In some cases, they continue, different versions of these rules are found in the writings of a single author. These “rules” are sometimes described by other scholars as “private creeds,” but are essentially the same thing.

Kinzig and Vinzent find no extant evidence of declaratory creeds—formulated as "I /We believe…”—from the first three centuries CE, although some scholars hypothesize that they may have been used in churches earlier. By the early fourth century, however, there is indeed evidence that proto-orthodox Christians in different regions were comparing and debating “rules of faith” and formulating creeds as they refined church doctrine.

What made the creeds more than simple differences of opinion among different Christian churches was their adoption and codification by political rulers. The council that drafted the Nicene Creed in 325 was convened by the Roman Emperor Constantine, who had reunited the Western and Eastern halves of the empire and was eager to tamp down disorder among different Christian sects.

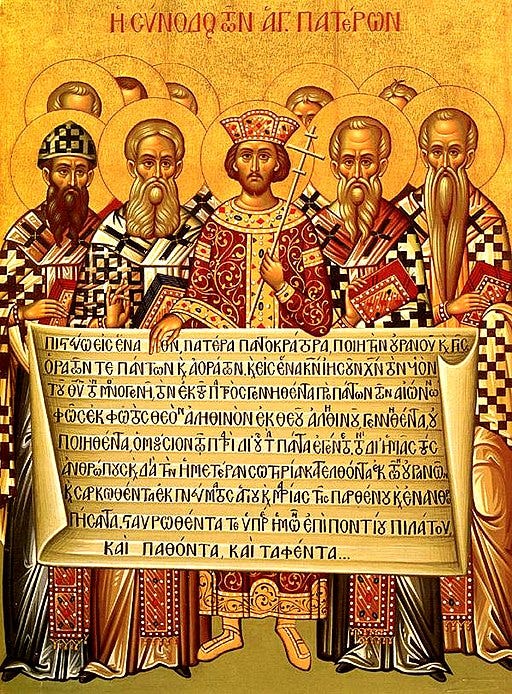

An icon showing the Roman Emperor Constantine, along with his bishops, and the 381 text of the Nicene Creed. Unknown artist, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Although precursors of the Apostles’ Creed were in use around the end of the fourth century, the current version was finalized in the early ninth century, during ecclesiastical reforms under Charlemagne, the leader of the Carolingian Empire (which encompassed most of Western and Central Europe), who required its use throughout the churches his kingdom. It was later adopted by the Roman Catholic Church. (The Apostles’ Creed is not used by Eastern Orthodox churches.)

Christianity Without Creeds?

As key tools of the proto-orthodox churches, the creeds were enormously successful, as their continued use today attests. The beliefs the creeds affirmed became—and continue to be—the core beliefs of a large majority of organized Christian churches. The focus they provided proved to be powerful.

But along with focus comes narrowness. For me, the diversity of beliefs in the early Christian churches offers a richer and more capacious spiritual circumambience in which to think about the revelations of Jesus and his lessons for life and society.

Further Reading

Ehrman, Bart D. 2003. Lost Christianities: The Battle for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Fairbairn, Donald, and Reeves, Ryan M. 2019. The Story of Creeds and Confessions; Tracing the Development of the Christian Faith. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.

Kinzig, Wolfram, and Vinzent, Markus. 1999. “Recent Research on the Origin of the Creed,” The Journal of Theological Studies. Vol. 50, No. 2, Centenary Issue 1899—1999, pp. 535-559.

Litwa, M. David. 2022. Found Christianities: Remaking the World of the Second Century CE. London, New York, Oxford, New Delhi, Sydney: t&t Clark.

Great read.