My Christian Role Model

I owe much of my affinity for Christianity to my grandfather, a joyful and humble man who manifested the teachings of Jesus in everything he said and did.

In my very first Substack post, I described my childhood involvement in the Lutheran church and my subsequent disengagement from organized religion in my teens, despite the fact that the main messages of Jesus have continued to resonate with me throughout my life. As I look back, I’ve realized one of the main reasons I remained comfortable with Christianity as a spiritual, moral and ethical compass was the example of my grandfather, whose approach to life seemed guided by the teachings of Jesus to a much greater extent than anyone else I have personally known.

My grandfather was fifty-eight years old when I was born in 1950, and eighty-three when he died in 1975. He was a bright presence throughout my childhood and early adulthood. He never lectured or scolded his grandchildren and only offered advice if asked—and then only if he had something positive to say. What we learned from him was entirely taught by example. He treated everybody with cheerfulness and respect. He was loathe to judge and inclined to assume the best in others. In my personal experience, he was never cross, irate, or angry. Looking back, I cannot remember ever hearing him raise his voice. I’ll tell a few stories that illustrate his approach to living below, but first let me set the stage of his life, which was eventful, successful, mostly happy, and definitely Christian.

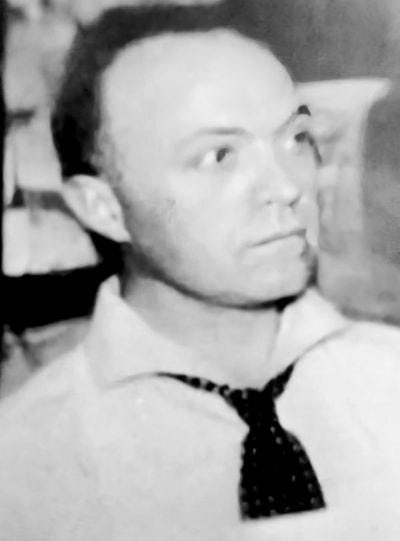

Ingwert as young man (detail from a larger photo reproduced below).

From the North Sea to North America

Ingwert Cornelius Braren was born on October 2, 1892, in the village of Oldsum on the Insul Föhr, one of the North Frisian Islands, a few miles off the coast of Germany in the Wadden Sea, as the coastal shallows of the North Sea from Denmark to the Netherlands are known. (Föhr had been part of the mainland until the St. Marcellus Flood of 1362, also called the Grote Mandrenke—the Great Drowning of Men—which washed away whole towns and villages, and significantly rearranged the coastal topography).

The North Frisian islands were under control of the various rulers of Denmark from the early Renaissance until the nineteenth century, when Prussia (later Germany), seized them after the Second Schleswig War and the subsequent Austro-Prussian War. Föhr became part of the German province of Schleswig-Holstein in 1867—an event that was to play a fateful role in my grandfather’s life. My mother remembered one of her grandfathers, who lived thought this period, remarking that he had kept different flags in the attic so he could switch them out when the rulership changed.

Föhr had a long maritime history. Frisians were widely regarded as expert sailors. A school of navigation was established on Föhr in the seventeenth century, which was successful and followed by several others. Whaling was the major economic activity in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Around 1700, more than sixteen percent of Föhr’s population of six thousand were whalers, and at the height of the whaling industry in the mid-eighteenth century, a quarter of all shipmasters on Dutch whaling vessels were from Föhr. It was a profitable business, and the island became quite prosperous.

But as the whaling business declined in the nineteenth century, so did the Frisian economy. Farming became the main industry, and the income it produced was barely sufficient to support the population and provide enough jobs. The custom of primogeniture—still in full force in the nineteenth century—meant that the eldest son would typically inherit the family farm, leaving few opportunities for their brothers, not to mention their sisters. This applied to Ingwert, the seventh child and fourth son of ten children.

One story I heard about my grandfather as a child was that he had a brother—Cornelius Friederik Braren—two and a half years his junior, who suffered from a serious disability or illness, could not walk, and died when he was six years old. My mother was told when she was a child that my grandfather—who himself would have been only eight years old when Cornelius died, had fashioned a kind of small cart in which he would tow his brother around the farm and village to keep him company.

By the time Ingwert was born in 1892 it had become common for young Frisian men to seek their fortunes elsewhere. Like thousands of others in the decades before him, he set off—for New York City—on the day after his church confirmation at age fourteen, where he found work in the delicatessen business, in which Frisian émigrés—including a few of his relatives—had already carved out a successful market niche, which they continued to hold into the mid-twentieth century.

Making it in New York—with a Grim Interlude

One reason that Frisians took to the U.S. was their native language—Föhring (Fah-ring), the local dialect of North Frisian, which is a close cousin of English. Old Frisian was very similar to Old English. (When my mother, who had become fluent in Frisian during several summer trips to Föhr as a child, was assigned Beowulf in an undergraduate English class, she found she could read it almost effortlessly.) Linguists say that modern Frisian is more closely related modern English than any other language, apart from those that themselves derive from Old English, such as Scots.

English, as a result, came easily to Frisians, and Ingwert learned it quickly. (He was also fluent in German, which was taught in primary school on Fohr, and could get by reasonably well in Yiddish.)

He worked in several delicatessens in New York, as well as at a few other jobs in places where Frisian relatives had settled, including a short stint at an illegal distillery in Florida (this was during Prohibition), where he recalled that they filled bottles with three different labels—scotch, rye, and bourbon—all from the same barrels of spirits).

In 1914, he returned to Föhr to spend the summer and to marry my grandmother—Clara Cornelia Olufs (born in 1897). World War I broke out, and he was drafted into the German army and soon shipped to the Russian front, where he remained until 1918. When asked about his wartime experiences, he said little about combat. He and his fellow infantrymen fought mostly in trenches, and were ordered by officers when to load and fire in unison. He said that he always aimed high over the opposing forces, for fear that he might inadvertently hit somebody.

Clara and Ingwert, just before or after World War I

The story he told that I remember most clearly was about the fellowship of the German and Russian soldiers. Late at night, he related, small groups of soldiers would sneak up to the front lines to barter with their opponents for common necessities like food, soap, tobacco, and newspapers (which were prized for their use as insulation for ill-fitting army boots during the Russian winters).

My grandfather was in demand on these mercantile forays because he could speak English. Once, he recalled, he struck up a conversation with an English-speaking Russian soldier, who had emigrated to Chicago several years before the war, and, like my grandfather, had returned to his homeland to marry and was instead drafted into the Russian army. He also recalled that the German and Russian soldiers would gather near the front-line trenches on Christmas Eve to sing hymns.

When the Soviet government withdrew from the war after the Russian revolution, in March 1918, Ingwert and tens of thousands of other conscripts were shipped to the French front, where the German army, outnumbered and outgunned at that point by the growing and well-supplied allied forces, fought a series of losing battles into the summer.

Sometime that summer, Ingwert’s unit was caught on open ground by an English biplane (likely returning from a bombing mission). It was his most dramatic war story: He would tell how the pilot strafed the troops with his machine guns—imitating their sound of the guns, and describing the grim look on the pilot’s face—and how he missed them on his first pass. But then the pilot circled around, coming in lower, and fired again, more accurately, and one of the rounds ripped through my grandfather’s left forearm.

He would then pull back his shirtsleeve to show an ugly scar—still vivid fifty years later—and then smile and say: “Luckiest thing that ever happened to me!” He was sent to a field hospital well back from the front line to be stitched up, and while he recuperated, the doctors and officers were so taken with his cheerful demeanor, popularity with the other patients, and general helpfulness that they had him transferred from his infantry unit to the hospital. He served there as an orderly until the formal end of the war in November 1918.

Ingwert made his way back to Föhr, mostly on foot, and not long after he and Clara married and left for New York, arriving just after the influenza epidemic of 1919. The delicatessen business was good. They lived in Harlem at first, but soon went to work for and came to buy another Frisian delicatessen in Park Slope, Brooklyn—a prosperous, tree-lined neighborhood abutting Prospect Park, one of New York’s most beautiful green spaces. Clara did most of the food preparation, making potato salad, coleslaw, desserts, and other delicacies every morning at dawn, and used to remark that the work she did before breakfast ensured the bills would be paid every month. Along with the job came a spacious apartment above the store.

Ingwert (in the white apron, left) in a promotional photo for Bond Bread, at his Brooklyn delicatessen around 1930.

“The Roaring Twenties” were a prosperous time, and the family accumulated savings and capital—as Clara would put it, by “making money American style and living Frisian style.” Their first child, my uncle, Cornelius Edward, was born in Brooklyn in late 1920—just two years after the end of the war. My mother, Lena Katherine, was born in 1922, followed by my uncle Edward in 1928.

One anecdote about Ingwert’s Christian ethics in action: In his delicatessen he insisted on serving customers in the order in which they had entered the store—including African-Americans who worked in nearby factories and warehouses—much to the disapproval of some customers who thought it more appropriate that they wait until the white customers had been taken care of.

1929 was another fateful year for Ingwert, showing again that he was a lucky guy. My grandfather’s landlord, who had become like a second father to him, decided to retire to Florida and sell the building—a stout brick three-story edifice that also housed two other stores and several rental apartments. He urged Ingwert to buy it, offering an advantageous price and making the case that real property in Park Slope would be a secure long-term investment that would provide independence as well as income.

At the time, the family’s savings were in banks and financial instruments overseen by an entrepreneurial Frisian investment adviser. As the family prepared for a summer-long vacation on Föhr, Ingwert realized he would feel more secure being away for months if he owned the building where he both worked and lived instead of keeping his money in intangible investments, and completed the deal.

Just weeks after the family returned to Brooklyn came the U.S. stock market crashed of October 1929. Much of the value of financial assets vanished over the next few years, and many of Ingwert’s friends and relations were ruined. Thousands of banks failed, and the Great Depression began. While none of this was good for the business, Ingwert had avoided the worst effects, and people still had to eat. It turned out that owning your own building, home, a successful delicatessen, and rental income was a pretty good way to ride out the hard times.

Left to right: Lena, Edward, Cornelius, Clara, and Ingwert Braren in the mid-1930s.

Another anecdote that illustrates my grandfather’s Christian nature: One of the apartments in the building had been rented to a quarrelsome and somewhat shifty couple for many years. An inspector from the local electric utility discovered one day that they had surreptitiously altered the electrical lines so that all of their power was being routed through my grandfather’s electric meter. Instead of bringing charges and evicting them—as the power company, friends and family members urged him to do—he noted that they had had a hard and unhappy life, and he decided they could remain as tenants.

The building my grandfather owned, at Eighth Avenue and Twelfth Street, in Park Slope in the 1930s. (The storefront is now a restaurant called Pasta Louise).

Ingwert eventually sold the building and the business in the mid nineteen fifties. He was in his sixties, and my grandmother Clara was ill with the cancer that would kill her, in 1957, at age 60, They bought a small apartment building in the Bay Ridge section of Brooklyn, near the house where I was raised. After Clara’s death, however, he missed the business and the human interaction that went along with it, and took a part-time job at our local delicatessen as a counterman.

He spent the rest of his time maintaining the building, visiting with his children and grandchildren, attending church, and reading. (He mainly read the bible in German, and his favorite books were the Psalms and the latter prophets—particularly Isaiah—who tend toward poetry and sermons that speak about justice, repentance, and future redemption.) He remained fit and active until the last months of his life in 1975. His funeral was held at the Lutheran church he had attended in Park Slope, a few blocks from the delicatessen he had owned and operated. A very large crowd attended.

Ingwert and Early Christianity

While this article if an homage to someone I loved rather than an inquiry into beliefs of the Christians of the first centuries CE, I feel there is a connection: As I look back on my life and my grandfather’s I realize that the world in which he grew up was much more like the world of the early Christians than the world we live in today. There were no automobiles or radios on Föhr when he was a small child. Electricity was just being introduced, but largely in the island’s only real town, Wyk auf Föhr (current population about 4,500). Life centered around the farm, the church, and the village.

Ingwert was baptized and raised in a Frisian Lutheran church and remained a faithful Lutheran churchgoer his whole life. Christianity had been introduced to the Frisian Islands in the late seventh century CE by a (Roman Catholic) Anglo-Saxon monk, bishop, and missionary named Willibrord (c. 658 –739), known as the “Apostle to the Frisians,” who later became the first Bishop of Utrecht in the Netherlands. Lutheranism became the dominant form or religion following the Reformation, but despite the theological and ecclesiological differences that had led to the creation of the Lutheran church, the basic, everyday teachings and beliefs of the of the Catholic and Lutheran churches were quite similar and were rooted in the Christianity of the early first millennium.

The Lutheran churches of Brooklyn that he attended had mostly been founded by German and Scandinavian immigrants in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and belonged to a denomination that emulated the “high church” Lutheranism of the home countries of their founders. My mother referred to their theology as being fundamentally flexible and forgiving, with “many paths to heaven.” They were sometimes at odds with other Lutheran sects in the U.S. that were more “low church” and fundamentalist.

I rarely talked about religion with my grandfather, but I am sure he never questioned the Christian faith he had known his entire life. He knew dozens of hymns by heart, including all their stanzas. (My mother recalled that the family would sing hymns at the dining table after Sunday dinner when she was a child.) He often quoted the bible. I can hear him saying one of his favorite verses, the opening of Psalm 122: “I was glad when they said unto me, Let us go into the house of the Lord.” Later in life, he would sometimes take his young grandchildren with him on weekends to the cemetery to visit Clara’s grave. He would tell the children to play by themselves, and would sit and talk to Clara, updating her on the latest family news.

When I think of him, the bible verse that comes most often to mind is the last line of the 23rd Psalm: “Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life, and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.” I think that is what he believed, and I aspire to believe it as well. I feel thankful to have known him, and have always felt that his spirit is never far from me.

Heartfelt and touching!