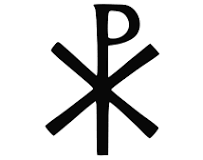

The Story of the Chi Rho Symbol

One of the earliest images of Christianity began as a sign of devotion to the "Prince of Peace," but later became a symbol of military conquest.

The “chi rho”—the logo for this newsletter—is one of the symbols used by the earliest Christians, formed by superimposing the first two (capital) letters—chi (X) and rho (Ρ)—of the Greek Χριστός (Christos, meaning Christ, Anointed One, Messiah). Also known as the Christogram, it said to have been revealed to the Roman emperor Constantine (who reigned from 306 to 337 CE) in a dream.

But, as in many other oft-told tales of the early Christian era, the story is murkier and more complicated than that. He certainly popularized it. But perhaps more importantly, the widespread use of the chi rho in the age of Constantine, as we will see, marks a consequential turn in the history of Christianity.

The Christogram

Ancient Origins

The chi rho symbol, in fact, predates Christianity by centuries. It is found on Egyptian coins from the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes in the late third century BCE. It was also used as a scribal notation in pre-Christian Greek manuscripts. Though the pre-Christian meaning is uncertain, scholars have hypothesized that the superimposed chi-rho in these cases stood for the first two letters of the Greek word χρηστός (chrestos), meaning good, or useful), and was used by copyists to highlight an important or quotable word or phrase, the way we might use an asterisk or a similar sort of mark today.

Early Christians adopted the chi rho symbol to represent Christ in religious manuscripts. It is one of several typographical symbols that scholars refer to as nomina sacra ("sacred names”). Others were used to denote “God,” “The Lord,” “Jesus,” “Jesus Christ,” and “the cross” (or “crucifixion”). The chi rho as a Christian symbol in this context is seen as early as the third century CE, and is likely older. (Surviving Christian artifacts of any kind from the first centuries are scarce.)

The earliest documented nomina sacra, according to scholar Larry W. Hurtado, was the staurogram—the superimposed Greek letters tau (T) and rho (P) –to represent σταυρός, (stauros, meaning cross—found in biblical manuscripts from the early- to mid-second century CE. Although the staurogram continued to appear, it never became as commonly used as the chi rho symbol.

The staurogram

Hurtado states that:

The nomina sacra should be counted among our earliest extant evidence of a visual and material “culture” that can be identified as Christian... [A]lthough the nomina sacra perhaps seem less impressive than other early Christian artifacts such as catacomb paintings, these curious abbreviations are also visual and physical expressions of religious devotion. Indeed, the nomina sacra can be thought of as hybrid phenomena that uniquely combine textual and visual features and functions; these key words were written in a distinctive manner that was intended to mark them off visually (and reverentially) from the surrounding text.

Many writers and scholars over the years have posited that the chi rho, (and other early Christian symbols), functioned as secret signs of recognition among Christian in times of persecution by Roman authorities. The first persecution, in 64 CE, was instigated by the Emperor Nero, who blamed Christians for starting the Great Fire of Rome that year; the last, and most severe and widespread, was the emperor Diocletian’s “Great Persecution,” from 303 to 312.

But in the second and early third centuries persecutions tended to be sporadic and localized, and many Christians lived openly throughout the Roman Empire, suggesting to some scholars that there was no need for secret signs. Justin Martyr, for example, (c.100 – c.165, one of earliest Christian writers whose work has survived), corresponded with Roman officials, explaining the harmlessness of the religion, and petitioning for legal forbearance.

Ten or so years after writing his most detailed apology for a Roman audience, however, Justin was charged with impiety during the reign of Marcus Aurellius, and arrested, convicted, and beheaded, likely in 165. So, although no conclusive evidence of the use of secret Christian symbols is known, the idea they might have been used doesn’t seem fanciful.

Constantine and the Chi Rho

The chi rho symbol went mainstream due to the efforts of Constantine, in the fourth century. He was the son of a previous emperor, and a brilliant politician and military leader. We know he the first Roman emperor who was sympathetic to Christianity, and in many ways favored it over other religions.

Three different accounts of “Constantine’s Dream” survive. One, told by the historian (and his son’s tutor), Lactantius, is that Constantine had a vision,the night before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, which he fought with a rival emperor on the outskirts of Rome in 312. (The bridge still stands and is in use, about four miles north of Vatican City). He was told in the dream to put a symbol “denoting Christ" on his soldiers’ shields, which he did the next morning. (He won the battle.) Lactantius’s description of the symbol is imprecise, and it sounds rather more like the staurogram than the chi rho.

Bust of Constantine, undated, unattributed Roman

The writer and church historian Eusebius, also a contemporary of Constantine, wrote two different accounts of this apparent miracle. In the first, written not long after the battle (and before he had met Constantine), he does not mention a dream or vision, but attributes Constantine’s victory to divine intervention.

In Eusebius’s second account, written many years later—and after he had gotten to know Constantine well, working for him as a speechwriter and chronicler—he writes that Constantine recalled his vision being at an earlier time and a different place than the Battle of Milvian Bridge, and that Constantine—along with his entire army—had seen a cross of light in front of the sun at noon, along with the Greek phrase Ἐν Τούτῳ Νίκα, rendered in Latin as in hoc signo vinces" (in this sign you shall conquer).

The next night, Eusebius relates, Jesus appeared in a dream to Constantine and told him to use the sign in battle, and goes on to describe the military standard that Constantine is known to have adopted later in his reign, which featured the chi rho symbol. (Critical scholars consider Eusebius to be an unreliable historian, and many speculate that his later account is either embellished or fabricated.)

Constantine’s Promotion of Christianity

Whatever the details, the story went on be become part of Christian lore. In 313, Constantine, then emperor of the western Roman Empire, met with Licinius, emperor of the east, and issued the Edict of Milan, decriminalizing Christianity and ending the persecutions for good. (After much internecine warfare and politicking, Constantine defeated Licinius in a later series of battles and established sole control of the entire empire in 324.)

In 325, Constantine convened the First Council of Nicaea, which produced the Nicene Creed (still in use). He eliminated taxation of Christian churches, showered them with money, and granted Christian bishops considerable administrative and financial powers. He built a lavish palace in the city of Byzantium, renaming it Constantinople (today’s Istanbul). He was baptized shortly before his death in 337, having made Christianity part of the mainstream of the Roman Empire—ultimately leading to its adoption as the official religion of Rome in 380. Throughout the fourth century, the chi rho symbol became ubiquitous, depicted on Roman coins as well as on military insignia, and appearing on everything from architecture to furniture and tableware.

Chi Rho wall painting. From a fourth century Roman Villa in Lullingstone, Kent; British Museum, via Wikimedia Commons.

Constantine was no choirboy. Apart from his bloody military conquests, he also had one of his sons, one of his wives, and a nephew executed for political reasons. Accounts of his religious views vary, but despite his Christian leanings, he also upheld the earlier, pagan, state religion of Rome throughout most of his life. His motives seem to have been a mixture of the personal and religious on one hand, and the practical and political on the other. He was attempting to unite support in an empire that stretched from the British Isles to Asia, in which the persecutions of Christians by his predecessors had caused division and unrest. He faced threats from political rivals and foreign invaders, and he overcame them brilliantly. His embrace of Christianity can be seen as one of his means to that end.

The Price Paid by the Church

The Roman embrace of Christianity was beneficial for the church in many ways—financially, socially, and in particular, in ending the threat of governmental persecution. But the church paid in other ways: It effectively abandoned many of the key teachings of Jesus—to love your enemies, to not repay violence with violence, and to avoid governmental entanglements.

Despite the tortuous efforts of later theologians, philosophers, and church officials to reconcile the teachings of Jesus with the imperatives of violence, conquest, oppression, and war—a topic I’ll explore further in a future post—Jesus had told his followers, “Blessed are the peacemakers. For they shall be called the children of God.” What had amazed the Roman world in the first centuries of Christianity was the willingness of Christian believers to suffer torture and death willingly rather than to defend themselves or to abandon their faith.

For more than two hundred years the early Christians had followed Jesus’s teaching, and the early church was resolutely pacifistic. The post-Constantinian church was anything but. It often acted as bloodthirstily and oppressively as its former oppressors—and still struggles with that cognitive dissonance to this day.

Further Reading:

Di Berardino, Angelo, ed. 2014 Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic.

Freeman, Charles. 2009. A New History of Early Christianity, New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Hurtado, Larry W. The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins. Grand Rapids, MI / Cambridge UK: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.