Thoughts on “Jesus and the Woman Taken in Adultery”

This famous New Testament story tells us something about how the Gospel stories came to be—and about the selective way that some Christians choose to ignore them.

The story of how Judean religious officials confronted Jesus with a woman who had committed adultery—and demanded his opinion on how she should be punished—is a litmus test of what Christians understand their religion to be about. Should she be stoned to death (the law of the land in Judea in the early first century of the Common Era) or not? If not, what should her punishment be?

In the Gospel story, Jesus, teaching on the Mount of Olives near Jerusalem, not only refuses to judge the unfortunate woman: He refuses to rebuke—much less punish—her. For readers who are unfamiliar with the passage, or may be a little rusty on the details, here it is (in David Bentley Hart’s lucid modern translation):

And the scribes and the Pharisees brought a woman who had been caught in adultery and, making her stand before everyone in the open, say to him, “Teacher, this woman has been caught in committing the very act of adultery; now, in the Law Moses enjoined us to stone such a person, so what do you say? (And they said this to test him, so they might have some accusation to bring against him.)

Jesus, however, bending down, wrote upon the ground with his finger. But when they continued to question him, he stood up straight and said to them: “Let whosoever among you is without sin be the first to cast a stone at her.” And again, bending down, he wrote upon the ground.

And hearing this [and being convicted by conscience,] they departed one by one, beginning with the older of them, and he was left alone with the woman before him. And Jesus, standing up straight, [seeing no one but the woman,] said: to her, “Madam, where are they? Does no one condemn you?” And she said, “No one, Lord.” And Jesus said, “Neither do I condemn you; go, from now on sin no longer.”

The Mount of Olives today. Photo by Hagai Agmon-Snir حچاي اچمون-سنير חגי אגמון-שניר, via Wikimedia Commons

What is most striking about this story is its unambiguous example of Jesus’s radical and uncompromising message of love and forgiveness. Two other things about this anecdote, which appears in the Gospel According to John, struck me as I read Hart’s translation, (which includes a long and illuminating footnote on the story’s history).

It tells us something of how the acts and sayings of Jesus were remembered by his followers, and how they wound up in the New Testament that we know today.

It shows that even in antiquity, some Christians were uncomfortable with the practical implications of Jesus’s teaching, as are many people who call themselves Christians today.

This last point struck me with particular force when—just as I reading Hart’s translation—I saw an online news story about the behavior of an American Christian pastor who recently found himself in a situation not unlike the one Jesus faced two thousand years ago.

A Tangled Textual History

The background of the story of “Jesus and the woman taken in adultery” is a good example of how little we know about the ways the stories and sayings of Jesus evolved from early oral traditions into the written gospel texts that Christian churches ultimately deemed to be authentic. Most scholars agree that the story was not written by the same person who wrote the Gospel of John. The vocabulary and writing style are different, and its placement in the gospel is awkward. (Modern critical scholars believe the gospel was written between 90 and110 CE—sixty to eighty years after Jesus’s crucifixion.)

The earliest extant manuscripts of John do not include the story. But it begins to appear in various manuscripts in the fourth century, and it is typically included in manuscripts from the fifth century onwards. Some of these put it in a different place in the Gospel than it appears today. Other manuscripts include the story in the gospel of Luke rather than in John. At any rate, the Roman Catholic Church had declared it “canonical” (authoritative) by the fifth century.

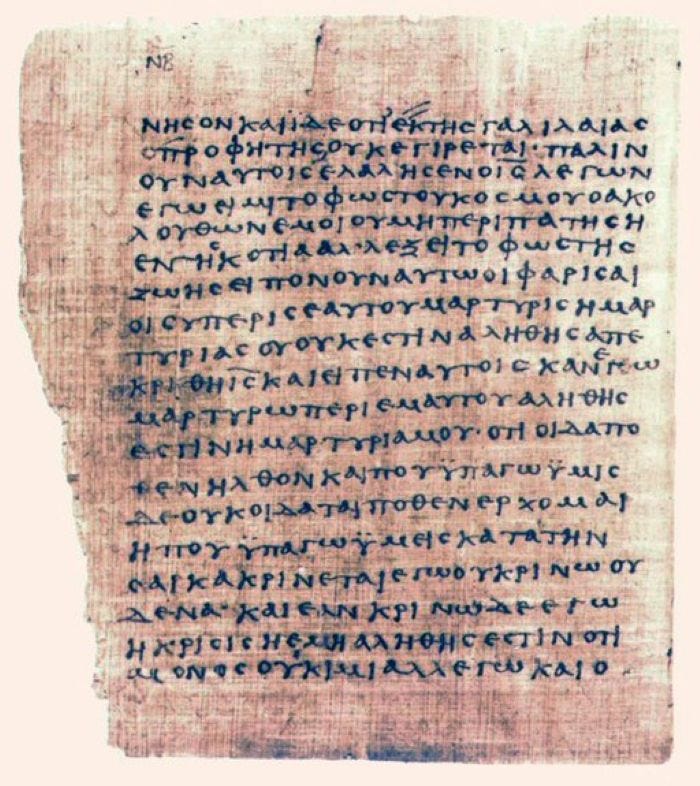

A papyrus text excerpt from the Gospel of John, circa 200 CE, that omits “the story of Jesus and the woman taken in adultery.” (Note: ancient Greek manuscripts were written entirely in capital letters, with no spacing between words and no punctuation.) Unknown writer. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

But before the gospels were written down in the rough forms of what we know today, the stories had circulated orally for decades—and perhaps also in other documents, some now lost, such as other gospels or compilations of the sayings of Jesus.

Thus, the curious history of the story’s occasional absence in John, and its peripatetic placement in the New Testament, does not mean it is an inauthentic, late addition. David Bentley Hart makes this case in one of the many erudite footnotes in his translation of the New Testament (which I’ve written about here). Hart writes:

There is good reason to think this episode may in fact be drawn from an older narrative source than the Gospel itself: there is a tale of a very sinful woman that the early second-century Christian Papias mentioned as being part of the lost Gospel of the Hebrews: the Syrian Didascalia (from the third century) cites “the “story of the adulteress”; the Constitutions of the Apostles (in a portion also from the third century) relates a similar story of a sinful woman whom Jesus refused to condemn; and both Didymus the Blind and Jerome mention the tale as appearing in many manuscripts before the end of the fourth century.

Moreover, the earliest texts of John do not merely lack the story; in its place are diacritical marks indicating that something (maybe the same story, maybe something else) has been omitted.

Augustine, in fact, aware of the story’s absence from many texts of the gospel, opined that perhaps it had been removed because of the offense it might give to pious souls unable to understand how Christ could excuse so grave a transgression with no more than an exhortation to sin no more.

It seems the story was something of a freely floating tradition, perhaps with very deep roots in Christian memory, one that was not originally firmly associated with any particular Gospel text, but that was inserted in various versions of Luke or John because it was too beautiful and too illuminating of Christ’s ministry and person to be left out of the church’s lectionary cycle (and hence out of scripture).

Not Getting the Message

Like the pious Christians referred to by Augustine in Hart’s note above, many 21st Christians are not comfortable with Jesus’s act of compassion towards the first-century “woman taken in adultery.”

In January of this year, a pastor at a fundamentalist church in Virginia caused a teenage woman in his flock to stand alone in front of her congregation to admit to, and ask forgiveness for, being pregnant and unmarried. The pastor’s punishment (other than the act of shaming her) was to forbid her or her family from holding a baby shower to celebrate her pregnancy. The event was filmed by an attendee, uploaded to the internet, and went viral, exploding like a mushroom cloud of outrage and criticism across the internet.

As I read further about this sad episode, I found that such shaming is commonplace in some American churches. I also found that some fundamentalist and evangelical preachers avoid discussing the biblical story at all (or do so only after making some comments about how there is doubt that John wrote it, undermining its authority).

Of course, any Christian familiar with the New Testament should instantly recognize that the “the story of the woman taken in adultery” is perfectly consistent with Jesus’s overall teaching. He told us in the Greatest Commandment that, after loving God, the second most important thing is to love your neighbor as yourself; that you should not judge lest you be judged; and, when asked how many times you should forgive one who sins against you, he said, “as many as seven times seventy times.”

I believe Jesus would have treated the young woman in Virginia very differently than her pastor did. And my guess is that he would have been fine with the baby shower.

Further Reading:

Hart, David Bentley. 2023 (Second edition). The New Testament: A Translation. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.